Energy Density of Foods

Understanding how food composition, meal volume, and energy intake connect through scientific research and physiological mechanisms.

Educational content only. No promises of outcomes.

What Energy Density Means

Energy density refers to the amount of calories contained in a given weight or volume of food. It is typically measured in kilocalories per gram (kcal/g) or kilocalories per 100 grams (kcal/100g).

Basic Definition: A food has high energy density if it contains many calories in a small weight. A food has low energy density if it contains relatively few calories for its weight.

Calculation Example: Broccoli contains approximately 0.34 kcal/g (34 kcal/100g), while almonds contain approximately 5.79 kcal/g (579 kcal/100g). This means almonds are more energy-dense than broccoli.

Understanding energy density provides a framework for examining relationships between food composition, meal volume, and overall energy consumption patterns.

Main Determinants of Food Energy Density

Several compositional factors influence how energy-dense a food is:

Water Content

Water contains no calories. Foods with high water content relative to their weight have lower energy density. Vegetables, fruits, and broth-based soups typically contain 80-95% water by weight, resulting in very low energy density.

Fibre

Fibre is a carbohydrate that contributes 2 kcal/g (compared to 4 kcal/g for digestible carbohydrates). High-fibre foods such as vegetables, legumes, and whole grains contribute less total energy per unit mass while adding volume to meals.

Fat Content

Fat contains 9 kcal/g, more than double the energy of carbohydrates or protein (4 kcal/g each). Foods high in fat relative to other nutrients—such as oils, nuts, seeds, and fatty meats—are considerably more energy-dense.

Air Incorporation

Foods that incorporate air, such as popcorn or aerated baked goods, have lower density than equivalent foods without air pockets. The structural composition affects both weight and apparent volume.

Gastric Distension and Early Satiety Signals

The physical sensation of fullness involves multiple physiological mechanisms. One significant pathway involves stretch receptors in the stomach wall.

Stomach Stretch Receptors: When food enters the stomach, it physically expands the organ. Stretch receptors (mechanoreceptors) in the stomach wall detect this distension and transmit signals to the brain via the vagus nerve. These signals contribute to the perception of fullness and can influence meal termination.

Gastric Volume: The volume of food material in the stomach is a distinct factor from energy content. Two meals of identical calories but different volumes may produce different satiety responses through stretch receptor activation alone, independent of caloric content.

Latency Considerations: Stretch-induced satiety signals develop relatively quickly (within minutes of food consumption), while other satiety mechanisms such as nutrient sensing develop over a longer period.

Nutrient Sensing and Post-Ingestive Feedback

Beyond physical distension, the body detects the presence and composition of nutrients through specialized sensory systems in the gastrointestinal tract.

Intestinal Nutrient Detection: Chemoreceptors and other specialized cells in the small intestine detect macronutrients (carbohydrates, proteins, fats) and send signals to the central nervous system. This nutrient-sensing pathway develops over minutes to hours post-ingestion.

Satiety Cascade: The overall sensation of fullness and satiation involves overlapping mechanisms: sensory properties (taste, smell, texture), cognitive factors (learned expectations about portion size), early mechanical signals (gastric distension), and delayed nutrient-detection signals (intestinal chemoreception).

Individual Variation: The strength and timing of these mechanisms vary between individuals based on genetic, metabolic, and experiential factors. Laboratory studies often show variability in satiety responses even when meals are controlled for energy content and composition.

Laboratory Studies on Isoenergetic Meals

Controlled feeding studies have examined how energy density of meals relates to subsequent hunger and energy intake.

Preload Study Design: Researchers typically give participants a standardized "preload" meal of fixed energy content but varying energy density (for example, 500 kcal of low-density vegetables or 500 kcal of nuts). After a delay, participants are offered an ad libitum test meal where they can eat as much as they desire.

Observed Outcomes: Many studies report that low-density preloads result in lower subsequent energy intake compared to high-density preloads of equal calories, although the magnitude of this effect and individual variability are substantial. Some studies find minimal differences, particularly over longer time horizons.

Mechanistic Interpretation: Researchers attribute differences partly to gastric distension from the larger volume of low-density food and partly to nutrient-sensing differences. However, cognitive and learned factors (awareness of eating a "large" meal) may also contribute.

Observational Patterns in Free-Living Diets

Outside the laboratory, population-level observations show relationships between dietary energy density and total energy consumption.

Epidemiological Findings: Large observational studies have found that individuals consuming diets higher in energy density tend to report higher total daily energy intake. However, these associations are correlational and confounded by numerous other factors (food preferences, portion size norms, physical activity, etc.).

Diet Composition Patterns: Diets lower in energy density tend to include higher proportions of vegetables, fruits, legumes, and whole grains. Diets higher in energy density tend to include higher proportions of processed foods, added fats, and energy-dense snacks.

Causality Uncertainty: Whether energy density itself is causally related to total intake or whether association reflects correlated dietary patterns remains an open question. Randomized controlled trials would be necessary to establish causality more firmly.

Food Examples by Energy Density Category

Foods can be categorized by their approximate energy density. These categories provide rough reference points for understanding food composition:

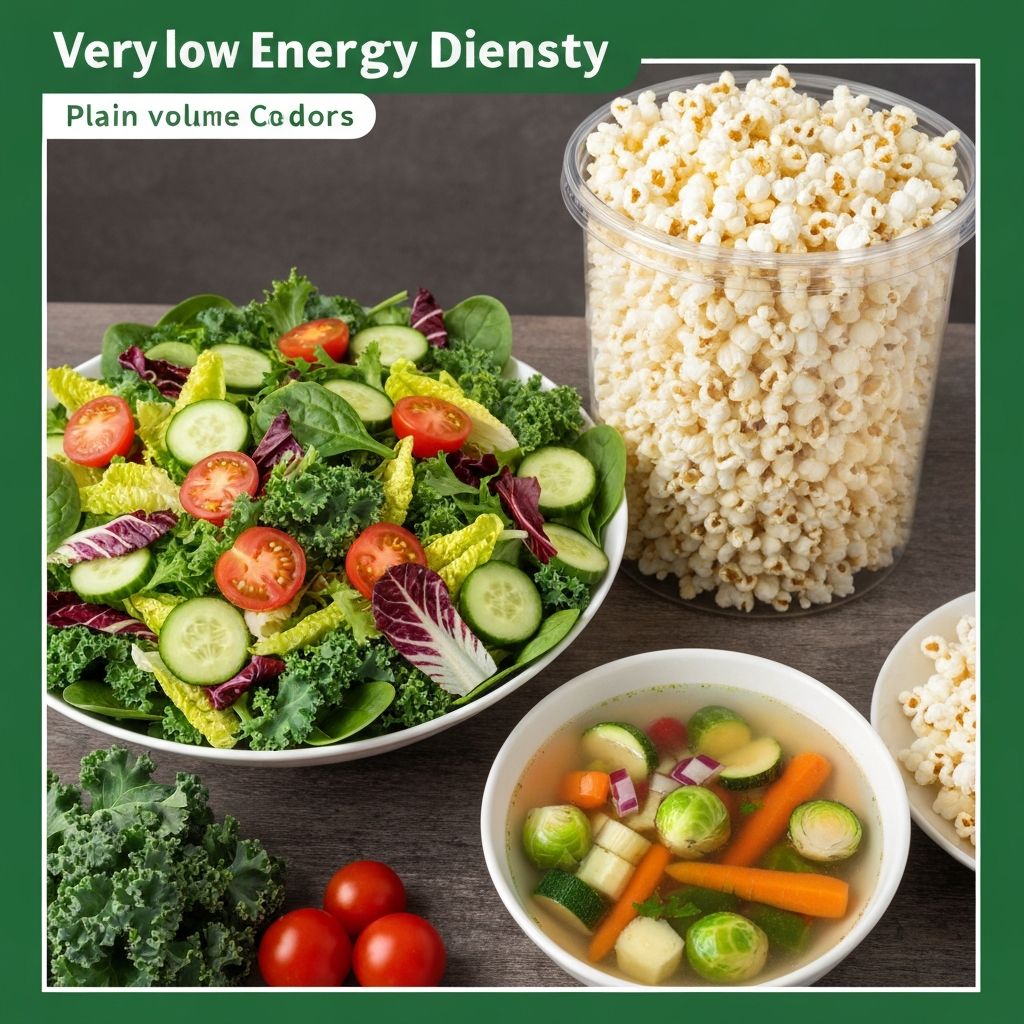

Very Low Density

0.1–0.5 kcal/g

Leafy greens, broccoli, cauliflower, cucumber, tomato, watermelon, strawberries, vegetable broth

Low Density

0.5–1.5 kcal/g

Most vegetables, legumes (beans, lentils), whole grains, plain popcorn, apples, pears

Medium Density

1.5–3.0 kcal/g

Lean meats, fish, cheese, bread, pasta, rice, avocado

High Density

3.0–9.0 kcal/g

Nuts, seeds, oils, chocolate, butter, processed snacks

Related Articles

How Water and Fibre Determine Energy Density

Explore the compositional factors that make certain foods less energy-dense despite satisfying volume.

Read More →

Gastric Volume and Meal Termination Signals

How physical stomach distension contributes to satiety and meal stopping signals.

Read More →

Laboratory Findings on Energy Density Preloads

Summaries of controlled studies examining meal volume and subsequent intake patterns.

Read More →

Dietary Energy Density in Observational Cohorts

Population-level patterns showing relationships between diet composition and total intake.

Read More →

Very Low Energy Density Food Examples

Detailed profiles of vegetables and broths with minimal caloric content per volume.

Read More →

Higher Energy Density Foods Comparison

Analysis of nuts, oils, and processed items with concentrated caloric content.

Read More →Frequently Asked Questions

Caloric content is the total energy in a food (measured in kilocalories). Energy density is that energy divided by the weight or volume of the food. Two foods can have the same caloric content but different energy density if they have different weights. For example, 100 calories of broccoli (low density) occupies much more volume than 100 calories of nuts (high density).

Water contributes weight and volume to food but contains no calories. Foods with high water content—such as lettuce (95% water) or watermelon (92% water)—are less energy-dense than the same foods after water removal. This relationship holds regardless of other nutritional composition. Higher water content generally correlates with lower energy density.

Fibre is a type of carbohydrate that contributes approximately 2 kcal/g, compared to 4 kcal/g for digestible carbohydrates. Foods high in fibre add volume and weight without proportionally increasing energy content. Additionally, many high-fibre foods (beans, vegetables, whole grains) also contain substantial water, further reducing overall energy density.

Fat contains 9 kcal/g, significantly more than carbohydrates or protein (4 kcal/g each). Foods high in fat content—oils, nuts, seeds, fatty cuts of meat—are substantially more energy-dense than lean proteins or carbohydrate-based foods. A small amount of fat adds considerable energy without proportionally increasing weight or volume.

Stretch receptors are sensory nerve endings in the stomach wall that detect physical distension. When the stomach fills with food, these receptors send signals to the brain that contribute to the sensation of fullness. This mechanism can operate independently of caloric content: a larger volume of low-calorie food may activate these receptors as much as a smaller volume of high-calorie food, potentially affecting satiety and meal termination.

No. Energy density is one factor among many that influence hunger, satiety, and food intake. Cognitive factors (portion size expectations, learned associations), sensory properties (taste, texture), nutrient composition (protein, carbohydrates, fats), individual metabolic differences, and environmental factors all play roles. Laboratory studies show individual variability in response even to controlled manipulations of energy density.

Laboratory preload studies show variable results. While many studies find that low-density preloads reduce subsequent energy intake, the effect is not universal or uniform across individuals. Some people show stronger satiety responses to physical volume, while others do not. Long-term compliance, food preferences, and dietary habits may matter more than acute satiety responses for sustained patterns of energy intake.

Explore More on Food Composition and Intake

Densivor provides educational information on energy density, food composition, and the physiological mechanisms connecting meal characteristics to energy intake patterns. Browse our resources to discover detailed explanations of how water, fibre, and fat content determine energy density, how physiological satiety mechanisms work, and how laboratory and population-level research examines relationships between food characteristics and overall food consumption.